About John Wise

About Me

Welcome to my story! Explore milestones by clicking events on the timeline below.

Childhood & Early Life (1983–2002)

I was born in 1983 at a naval base in Portsmouth, Virginia, but my early childhood unfolded across small towns near Dayton, Ohio and Gainesville, Florida. Until I was about eight, I lived with both my parents, but that changed after their divorce: my mother and I left Florida to return to Ohio, moving in with my grandparents. Those years were marked by constant upheaval -- frequent moves, switching schools, and the ongoing challenge of finding a sense of stability and home.

School, for me, was as much about learning to adapt as it was about academics. The constant moves meant bouncing between the Ohio and Florida school systems, which varied wildly in quality. That disruption left me disenchanted with school itself -- I felt more like I was being processed through a system than truly seen or supported. Even though I was often placed in honors or advanced classes, I did poorly overall: I'd sleep through most of my coursework, ignore homework, but still manage to scrape by thanks to high scores on final exams and standardized tests like the FCAT (or whatever version was current back then). I dropped out of high school at sixteen, having only completed ninth grade (after repeating it once).

Incarceration (2002–2021)

In 2002, at age eighteen, I entered the Florida Department of Corrections with a 22-year sentence. Having so much time to serve at such a young age -- 22 years was literally longer than I'd been alive -- was impossible to truly grasp. Although I was initially housed with other "youthful offenders," I was incarcerated in adult prisons from the very beginning (Okaloosa Correctional Institution); I had to adjust very quickly.

While I was always skilled at staying out of administrative trouble -- I rarely received disciplinary referrals -- just surviving in prison still always meant being "in trouble" in some way. I finally managed to get a foothold on stability after Hurricane Ivan in 2004, when the facility where I was housed in the panhandle was hit hard by the storm. I volunteered for the roofing crew afterward, just to keep busy and learn something new. It was actually fun.

A few weeks into that work, I took a day off because I wasn't feeling well. That happened to be the day a shingle-cutting knife went missing -- a knife that, weeks later, was discovered to have never been assigned to our crew at all. Still, the entire roofing crew -- about fifteen people -- were sent to confinement pending an investigation. Since the roofing crew was technically part of maintenance, I suddenly became the only maintenance worker not in confinement, the de facto "head maintenance" worker.

My time as the maintenance worker became a turning point. I did well enough in this emergency role that I was kept on the general maintenance crew for the rest of my stay at that institution, all the way until 2010. Eventually, I worked my way back to being the head maintenance worker (not a formal position, but I had the most seniority and responsibility). My primary job was keeping the kitchen equipment running: daily battles with the dish machine, kettles, ovens, and everything else that kept the place going.

In mid-2010, I suddenly found myself at a new facility: Century Correctional Institution. The Florida Department of Corrections has nearly 60 institutions across the state, and location instability is a built-in part of incarceration -- a carceral tool to keep people compliant and off balance. It was remarkable that I'd managed to stay at my previous location for as long as I did. My first year or so at Century were another period of adjustment and survival, mostly spent living the "tattoo life." I was the "spook" for the most prominent tattoo man at the facility. Since tattooing is prohibited, my role was to be constantly vigilant -- always keeping an eye on the correctional officers so the tattoo man wouldn't get caught. It was a full-time job, and my payment came in the form of tattoos. I got a lot of tattoo work.

Around mid-2011, something shifted -- an invisible but pivotal turning point in my life. Frequent facility lockdowns due to riots had me spending more and more time in the prison library. One day, I found a donated college textbook: something like Physics and Its Applications in Engineering and Design. The pictures looked cool. The library's strict borrowing policies meant I couldn't check it out, so I simply stole it. Back at the dorm, though, I realized the book was full of math I couldn't begin to understand. I returned it on my next trip and instead took a College Algebra textbook -- but the results were the same. I couldn't even get through the prerequisites chapter.

Giving it one more shot, I traded the College Algebra book for a high school algebra textbook -- an old edition from the late 1960s. Inside the front cover was the name of its only previous owner: Maria, a student from San Juan, Puerto Rico, who had filled the margins with notes and problem attempts. Maria became my imaginary study partner as I worked through every page and every problem. The change in me was so profound it felt like being struck by lightning. After finishing that book, I rapidly tackled more -- college algebra, precalculus, trigonometry, several calculus books, differential equations, predicate calculus and recursion, formal proof writing, anthologies of mathematical history, chemistry, physics, biology -- anything I could get my hands on.

Eventually, my informal study led me to help others around me who were pursuing their GED -- the only educational program available to most people incarcerated in Florida, including at my facility. That quickly led to my hiring by the Education Department as a GED instructor. At first, I was hesitant to take on the role, but I found it very rewarding working with my peers and witnessing their own transformations. There was also a practical benefit: after working for a year as a certified "Inmate Teaching Assistant" (ITA), I became eligible for an "Institutional Need" transfer to the facility of my choice.

Wanting to earn a trade certification before release, and under the impression that Tomoka CI offered an AutoCAD program, I completed my year as an ITA and put in for a transfer to Tomoka. Upon arrival, however, I discovered that the "vocational program" was informal and, by that point, no longer running. Previously, it had been an "AutoCAD Certificate" program created and led by an incarcerated individual -- without any formal credit or credentialing -- and that person had been transferred out not long before, much like the upheaval I'd experienced myself.

The program, even when available, was only open to those enrolled in a "Faith and Character-Based" program -- an intensive, inter-institutional residential therapeutic community -- as they controlled the only computers with AutoCAD software. Reluctantly, I joined that program and completed the required year. Over time, I became a program facilitator, and eventually a facilitator trainer, roles which overlapped with and enhanced my work as a GED instructor. Eventually, I ended up restarting and myself teaching the AutoCAD course.

After so many years of informal study, I found myself wanting more. In mid-2016, I managed to enroll in my first formal program, the Cleveland Institute of Electronics's certificate program in Industrial Electronics with PLC Technology. Shortly after, I joined the inaugural class for the Second Chance Pell program -- which required a transfer to Columbia Correctional Institution Annex.

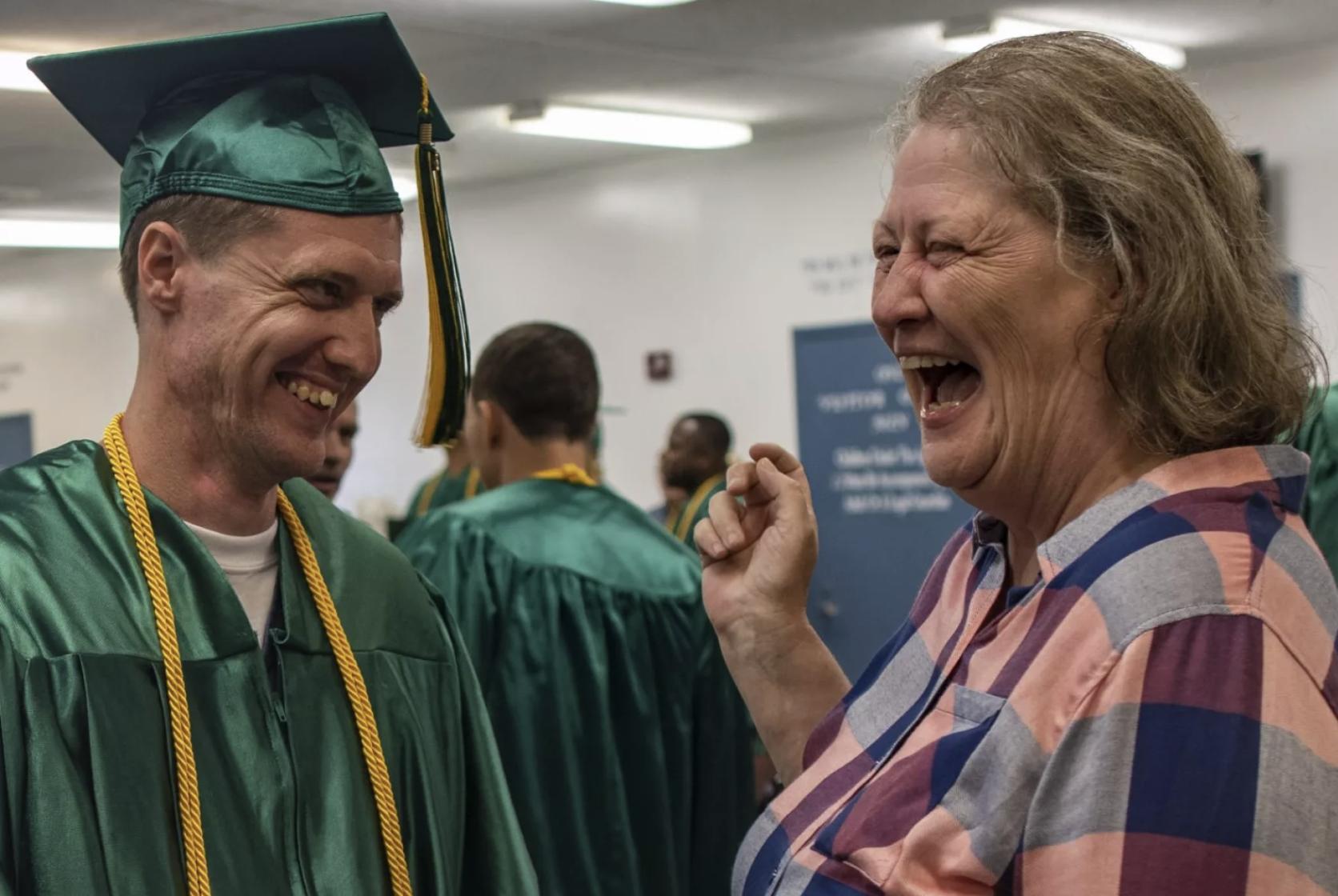

I really loved my time there. I earned my Associate in Arts degree through Florida Gateway College (graduating Summa Cum Laude), while many of my peers pursued and earned Associate of Science degrees in Environmental Science Technology. (Alongside those courses, I also completed a few correspondence courses with Ohio University) I had the privilege of acting as a de facto tutor during this period, and was even allowed to use the program classrooms to host group tutoring sessions.

One of the proudest moments in my life, moreover, was being selected as the Ceremonial Speaker at our graduation ceremony.

After graduation, I was given the rare opportunity to transfer to any FDOC facility I chose. I decided to return to Tomoka Correctional Institution, mostly because the Community Education Project -- a program developed by professors at Stetson University -- was, by that point, offering formal, credited coursework.

I had previously participated in CEP informally at Tomoka before transferring for the SCP program at Columbia, so I was excited to return to those classes. During my time there, I managed to take two courses formally -- American History and Philosophy (where our class textbook was Moby-Dick by Herman Melville!). Unfortunately, the start of the global COVID-19 pandemic canceled all in-person classes for the remainder of my incarceration.

Post-Incarceration (2021–Present)

I'm not going to lie -- the time since my release from prison has been some of the most challenging of my life. When I was inside, I looked forward to getting out with anticipation, to be sure, but also with a great deal of fear -- I'd spent full-on half my life inside.

My first steps were educational. I enrolled at Santa Fe College in Gainesville -- not into a degree-bearing program, but to pick up some formal coursework I was missing along the way. I was released in April, enrolled in college in May. Just three courses over the summer semester, but it was good momentum.

Next, I enrolled at Indiana University East online, where I completed my B.S. in Data Science, graduating in December 2023 with a 3.89 GPA, recognition as Outstanding Student in Data Science for 2023–2024, and Dean's List for 2022–2023.

That's been the easy part.

Employment has been much more of a challenge. While I did a little bit of work within my first few weeks of release with researchers from Stetson and Harvard Universities on a project called COVID Prison Stories -- an archival effort meant to document the impacts of the pandemic on those incarcerated or recently released -- IRB concerns halted the project in its tracks (gathering the stories of those currently incarcerated exposes them to harm and retribution from the carceral system). So, I don't have a project page to link to for that, and I often don't list it on my resumes.

Photo credit: teamdicky.blogspot.com.

I actually consider my first "real" job post-release to be one of my fondest moments in life -- my time at Jimmy John's Gourmet Sandwiches as a delivery cyclist on the University of Florida campus and downtown Gainesville. I loved that job -- for someone just getting out of prison there was nothing more joyous or liberating than the simple accomplishment of being so good at delivering sandwiches on a bike very fast. It was also very anchoring, learning the layout of Gainesville by developing routes and shortcuts. I learned where every rock and hole in the street was.

That's not to say I didn't also do everything I could to be involved with my community in other ways. Within the same week I started at Jimmy John's, I also started a 9-month fellowship at Community Spring.

My fellowship at Community Spring marked a real turning point in how I understood community work and systems change. Community Spring centers those most affected by poverty and incarceration, building power through direct action, grassroots advocacy, and genuine partnership. During my nine months there, I co-founded and led the Lighthouse Campaign for Affordable Housing -- driving policy research, coalition-building, and public communication to address housing inequity. I learned to manage projects and partnerships in a mission-driven, collaborative environment, and I saw firsthand how lived experience, when trusted and resourced, can fuel real solutions. Their belief in me, as someone newly released, gave me confidence and the tools to make an impact. Community Spring isn't just a nonprofit -- it's a movement for economic justice in Gainesville, and I'm grateful to have been part of it.

After my fellowship at Community Spring, I was energized to do more -- not just for myself, but for others still navigating the barriers I'd known. I launched the Education Access Partnership, a nonprofit initiative aimed at bridging the gap between local colleges and universities and the Florida Department of Corrections. My goal was straightforward, but ambitious: help bring higher education opportunities into the hands of those currently incarcerated.

I made significant progress. I networked with college faculty, correctional staff, and other local nonprofits, building partnerships and trying to untangle the policy knots that keep education out of reach behind bars. For a while, it felt possible to move the system forward -- to serve as a bridge, an honest broker between worlds.

But the reality was, in that role, the Florida DOC still held power over my life. Even as a "free" person, I felt the weight of their authority pressing down on every decision, always reminding me that my professional and personal future could be influenced by people in uniform, far from any real accountability. Eventually, I had to make a difficult decision for my own health and sense of agency: I chose to call off the project, stepping back rather than continue to feel like my fate was still controlled by the system I was working to change.

That experience changed me -- it taught me about boundaries, about the limits of what one person can do, and about the importance of protecting your own wellbeing while working for justice. It also helped clarify my purpose: I want to use my skills and experience to create systems and tools that don't depend on institutional gatekeepers, but instead put real power in the hands of impacted people and communities.

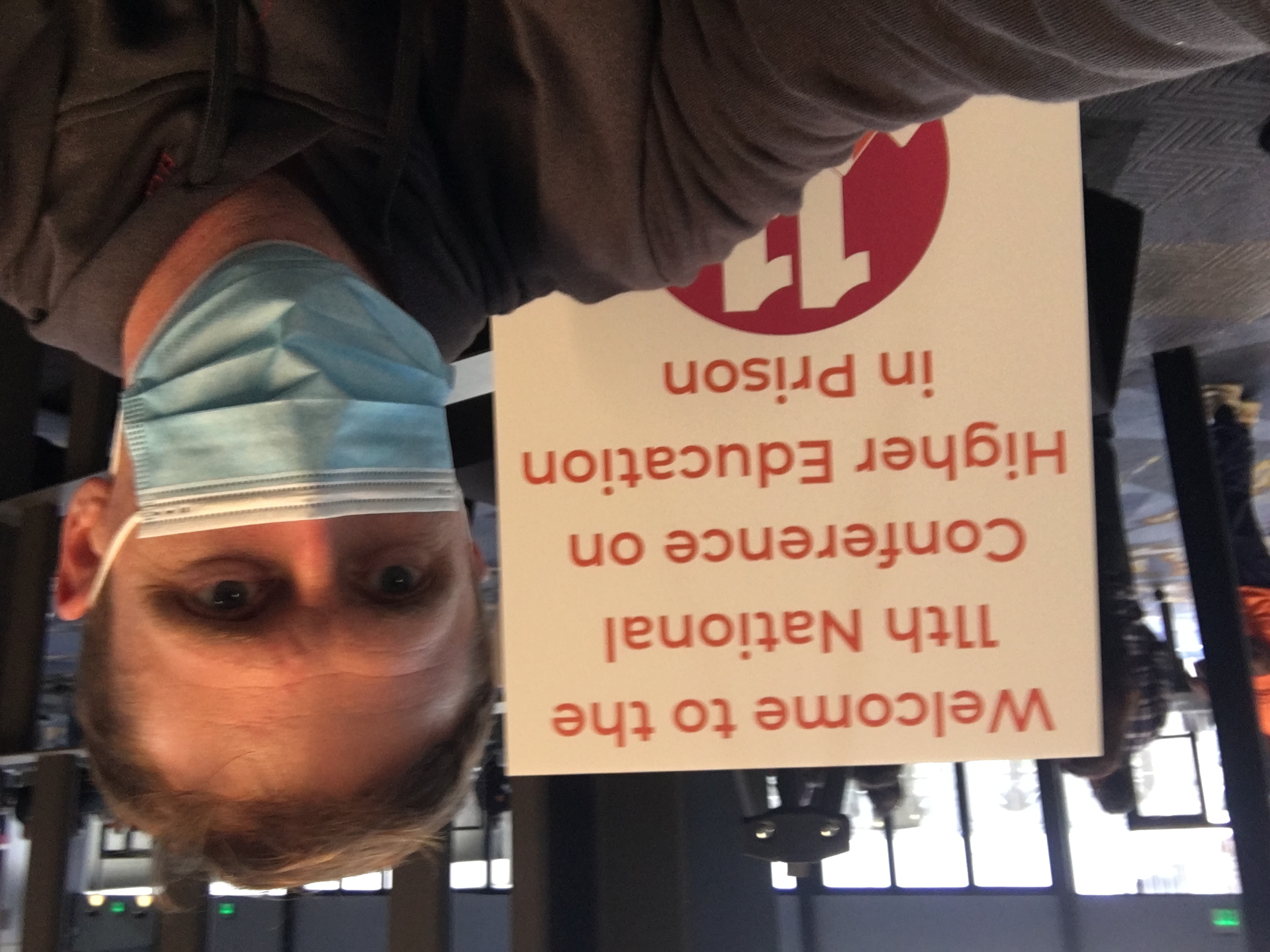

In 2023, I interned with the University of Utah Prison Education Project. At first, I focused on evaluating the Education Justice Tracker (an application designed to deliver important institutional data to higher education-in-prison program administrators) and presented my findings at the 2023 Cornell University Prison Education Project Symposium. That was a great experience -- sharing a space with people who actually care about making education in prison real.

But after the symposium, my work turned to something that left me frustrated, honestly: the total lack of real public access to institutional data on incarceration. I spent weeks trying to track down even the basics; I kept hitting brick walls. The information that does exist is usually scattered, outdated, and hidden behind agency websites that feel designed to make you give up. It drove home for me just how tightly institutions still control the story, even in the so-called "public" record. My public records requests were all rebuffed with disdain. That frustration didn't stop me (not permanently, anyway) -- if anything, it made me more determined to figure out ways to open things up for others who need the data, whether they're family members, journalists, or people inside themselves.

After my internship, I honestly hit a wall. The constant frustration of running into closed doors and hidden data left me burned out and angry. I needed to step back -- so I went for a lot of long walks, in a lot of Gainesville parks, just trying to find some peace and perspective. I reached out for help, and -- thankfully -- I found it at Released Reentry Center. That time let me recalibrate, get my footing again, and think more clearly about where I want to go next.

Graduate School (2024–Present)

In late 2024, I set my sights on graduate study in artificial intelligence. I applied to the University of Florida's new MS in AI Systems program. What followed was six months of silence and bureaucracy. After multiple attempts to get an answer, I learned that I'd been recommended for admission by the program itself, but that UF had flagged my application for additional review solely because I checked the box indicating a criminal record. I was shuffled into the university's "Student Conflict Resolution" process, which meant writing an exhaustive personal statement and submitting official court records from over two decades ago. The decision went up the chain, and I was ultimately denied. My appeal was summarily rejected without explanation or hearing.

Instead of waiting around -- and with the help of my incredible former professors, who pointed me toward new programs and wrote strong letters of recommendation -- I applied to four more schools in the space of a week: Purdue, RIT, Johns Hopkins, and Syracuse. Purdue wanted to run me through the same "behavioral review" gauntlet as UF, so I withdrew. But Johns Hopkins and Syracuse both offered me admission. I chose Syracuse.

The School of Information Studies (the iSchool) at Syracuse is the real deal -- one of the most respected programs in the field, and a place that genuinely values lived experience, resilience, and real-world impact alongside technical chops. The MS in Applied Data Science program is a perfect blend of advanced technical training and a focus on the social, ethical, and human context of AI and data.

The difference in how I've been treated versus UF is night and day. From the beginning, the iSchool made it clear they saw my story, not just my record. Instead of hoops and hurdles, I got real encouragement -- a message from the program's dean that I'll never forget, telling me that he personally reviewed my application and "We're lucky to have you in our community, and I'm confident you'll thrive here."

As crushing as the experience with UF was at the time, I can honestly say I'm grateful for where it led me. If I hadn't been pushed to look elsewhere, I might never have found my way to Syracuse's MADS program -- and now, I couldn't imagine a better fit. I'm currently in my first semester, exploring the intersection of data science, transparency infrastructure, and criminal justice reform. My current focus is developing Model Context Protocol (MCP) infrastructure to make incarceration and law enforcement data radically accessible to journalists, researchers, and the public.

These days, I'm working with DataAnnotation Tech as a contract AI Data Trainer. It pays the bills -- and gives me something harder to quantify: a ground-level view of how AI models actually get built, where they break, and what "good enough" looks like in practice versus in press releases. The gig life has its perks, too. I get to choose when and how much I work, which is pretty wild after so many years where every minute of my time was controlled by someone else. As I move forward with my master's at Syracuse, I plan to keep at it -- partly for the income, partly because there's no substitute for watching models fail in ways their documentation never mentions. There's something strange about working on the bleeding edge of AI while holding so many critiques of where it's headed. And honestly, the whole thing still feels surreal: after my first ten years inside -- almost half my sentence -- I encountered my first (very restricted) access to a computer, and someone had to show me how to turn it on. Now I'm here, learning, learning, learning.